BED BY JENNIFER BROUGH

Published in SICK issue 2, 2020

Jennifer Brough (she/they) is a workshop facilitator and slow writer. She writes fiction, reviews, and personal essays exploring the body, gender, pain, art, and literature. She is working on a poetry pamphlet called Occult Pain. Jennifer is the founding member of resting up collective, an interdisciplinary sick group of artists.

@occultpain / @restingupcollective

• • •

Since moving in with my girlfriend and throwing out an old mattress and its base, I single-handedly assembled a sturdy wooden bed frame for a cloud-like memory foam mattress. As Gloria Hunniford’s mum once said, “Always buy a good pair of shoes and a good bed — if you’re not in one you’re in the other.” Far from a humblebrag, this task was significant for both comfort and creativity. For me, the bed has never just been a place of sleep but serves as a space for waking dreams and writing. In all of the flats and houses I’ve lived in since leaving home, I have had a desk perhaps twice, so the bed has been the alternative space on which to congregate with friends, conjugate with lovers, and create by myself.

As the sun is setting on my twenties, I have done a great deal of these things; collecting memories of dinners with friends, gatherings at university, intimacies and pillow talk. I have also, along the way, accumulated two chronic illnesses. Following an emergency operation for a twisted fallopian tube, I was informed, in a hand- controlled, firm hospital bed, that I had endometriosis. Another laparoscopy a few years later left me with fatigue, pins and needles in my hands and feet, trouble sleeping, and a long list of other symptoms. I hunted answers, pinballing between doctors and specialists until finally, fibromyalgia landed in my lap. Endometriosis sufferers are more likely to have other chronic conditions and I have found the two to be greedy co-dependent bedfellows, fighting for space and hogging the metaphorical duvet.

Pain, especially when it winds its way into women’s bodies, is a cruel phantasm. As Elaine Scarry wrote, “To have great pain is to have certainty; to hear that another person has pain is to have doubt.” This doubt has historic precedent when the medical community have considered women’s pain, particularly in the bodies of women of colour. Hysteria is a well- known whisper that lingers in doctors’ corridors, from the wandering womb in ancient Greece to the masturbate-the-mania-away of the 19th century, the uterus has been a site of blame and medical mystery for centuries. Even now, it takes on average seven and a half years for a diagnosis of endometriosis, a term coined in 1921. Before recent research acknowledged the racial bias in investigating the illness, it could be assumed from a Google image search the sufferers are solely cis white women slumped unhappily in armchairs. This perception is part of the reason that women of colour, trans, and non-binary people find getting a diagnosis and treatment even more difficult, with one study highlighting the popular myth that endometriosis predominantly affects white women, and another indicating strong pain killers were more likely to be prescribed to white people than minority ethnic groups.

As a society, we’re not wholly equipped to deal with ‘invisible illnesses’ — we don’t really have the language for them yet. Not as sufferers, carers, partners, friends, employers, or medical providers. In her essay On Being Ill, Virginia Woolf recognised that “incomprehensibility has an enormous power over us in illness” not only in the ways we communicate but in the ways we are (mis)understood. A visit to a pain clinic was one of the most demoralising medical experiences of my life. The clinic was a room of 40 to 50 people, two practitioners, and not enough chairs. The practitioners tried hard not to divert from their scripts — the two-hour session was mandatory if you wanted to meet with a physiotherapist, psychotherapist, and pharmacist — but when an elderly Jamaican man frustratedly interrupted, “I don’t want to learn about pain, I know how it works. I’ve got it. I want help. I’m here for help,” the session quickly fractured into murmurs of dissenting agreement. We were there to discuss something invisible. Something subjective. Something that was pressing on each of us in one way or another. Audre Lorde describes pain as an event, “an experience that must be recognized, named and then used in some way in order for the experience to change, to be transformed,” but in that room, all we could do was hurl recollections of our shared events at the practitioners who, despite their sympathetic nods, were ultimately as powerless to change things as we were.

There are times when I doubt the existence of my own invisible illness and start constructing grand adventures. If you can’t see it, it can’t hurt you, right? But while I aspire to hike Machu Picchu and climb pyramids in Teotihuacan, most days I can just about make it to the big Tesco and back. As another adage goes, this time not from the Hunniford family, wherever you go, there you are. I remember some of the rooms I’ve temporarily occupied around the world and how disappointing it was to feel exactly the same as I did at home, albeit with a better view. I think of Spain last summer, lying on crisp white sheets and dry heat, looking out at the sea that beckoned beyond a terracotta wall. While it’s quite hard to feel blue when you’re near a beach, a painkiller haze and bad cramps are unwelcome stowaways to the pain-free enjoyment you had imagined.

But, thinking on Lorde’s words, I remind myself that while pain will be a continual factor for the foreseeable future, it is “how we evade it, how we succumb to it, how we deal with it, how we transcend it” that is important. So, I have remade the bed, both literally and metaphorically transforming it from a passive rest place to an active site of creative thinking. Of course, I am far from the first person to pursue their passion horizontally, and while there are many famous beds throughout literature and art history, there are certain people I continually revisit for inspiration and acceptance.

My Bed, Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998) proved

to be a controversial piece, created after

a difficult breakup in which she didn’t

leave her bed for four days. The detritus

surrounding the bed — cigarette ends, period-stained underwear,

painkillers, empty vodka bottles, and

used condoms witnessed by a stuffed

dog — are commonplace symbol of those spiralling moments many have experienced following stretches

of emotional hardship. It has been

described as a self-portrait and though

the artist is absent, her presence is

imbued within it. Yet Emin herself said

that each time the piece is exhibited, it is further away from the person she

was when it was first shown 20 years

ago: “It gets older, and I get older, and

all the objects and the bed get further

and further away from me, from how I am now.” As time passes, we move

from bed to bed — throwing out sagging

mattresses, getting sturdier frames to

build the spaces we need, when we need

them.

Henry Ford

Hospital, Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo, too, created from her bed, turning both her recovery space and the pain and isolation she experienced through illness into art. She would go on to have over thirty surgeries in her life and spent many hours recovering and learning to be alone. The bed is a symbol that recurs in several of her paintings. Henry Ford Hospital (1932) depicts the artist naked and bleeding after a miscarriage. Six vein-like ribbons stretch out from her abdomen leading to a foetus, an orchid, a female abdomen, a snail (representing the slowness of the miscarriage), a pelvic bone, and an autoclave (a metal instrument used to sterilise medical utensils). It was her first painting on metal, using the style of Mexican ex- votos, Catholic folk art that depicted individual tragedies prevented by divine intervention. Kahlo entwines her grief in a format traditionally dedicated to saints, centring herself in a narrative that simultaneously invokes the mystic and mortality.

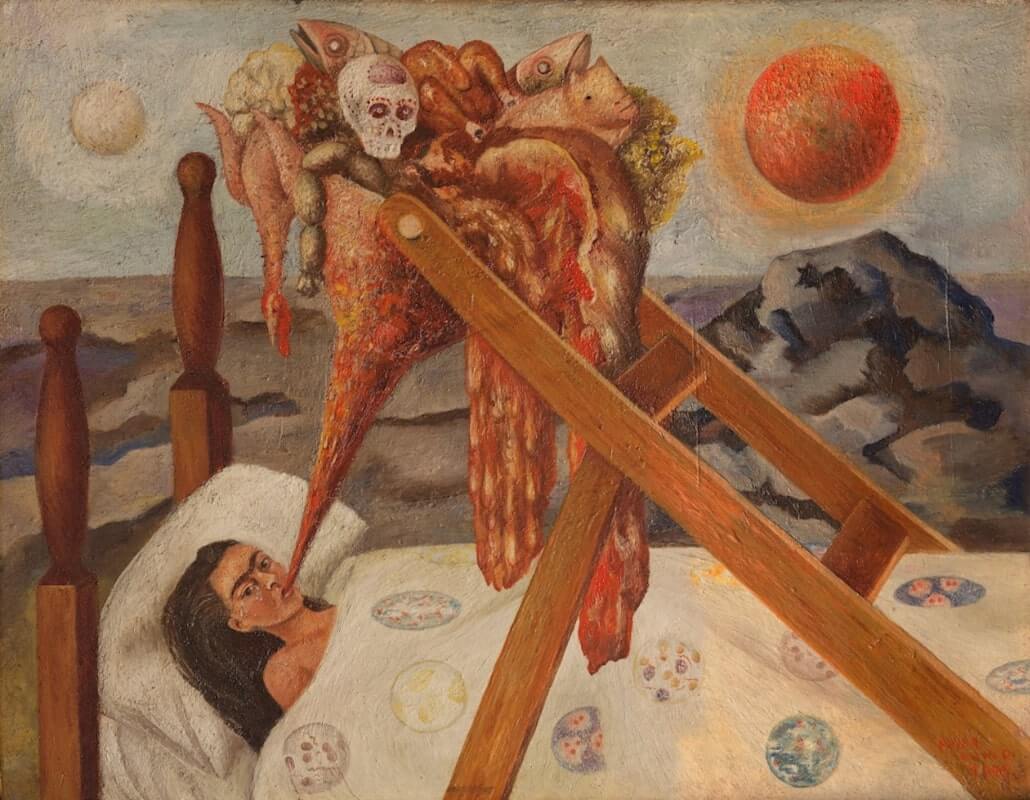

Without Hope (1945) shows Kahlo in another bed in an arid landscape, the sun and moon hanging in a murky sky. She is only visible from the shoulders upwards and is pinned down by a large wooden ladder supporting a feeding tube overflowing with fish, chicken, lamb, and a bright calavera as a small nod to death. Kahlo was between surgeries and suffering from a lack of appetite. To counteract her weight loss, her doctor prescribed a forced diet. Tears fleck her cheeks as she looks directly at the viewer, unable to intervene beneath the weight of the grotesquely abundant food. Kahlo spent much of her life in and around beds; even sending her vividly decorated four-poster to her 1953 solo show in Mexico City to wait for her when she was carried in on a stretcher, after arriving in an ambulance.

Without Hope, Frida Kahlo

Both Emin and Kahlo used the unwell self as subject matter in their confessional art and it is their willingness to use these vulnerable moments that makes their appeal widespread. In these works, beds are intimate spaces where the private and public self meet. They are creative sites, places in which the artists construct and unravel selves. Beds are spaces that hold our most vulnerable states, from desires and dreams to suffering and pain. Chronic illness has adjusted my pace to make me take time. Now I consider how I spend it before I must inevitably return to rest in bed. This is not a defeat, nor is suffering a way in which I define myself; rather, it is a form of self-care in slowness, a method of coping, of transforming and trying to transcend pain into a manageable practice.

Images

My Bed, Tracey Emin

Henry Ford Hospital, Frida Kahlo

Without Hope, Frida Kahlo